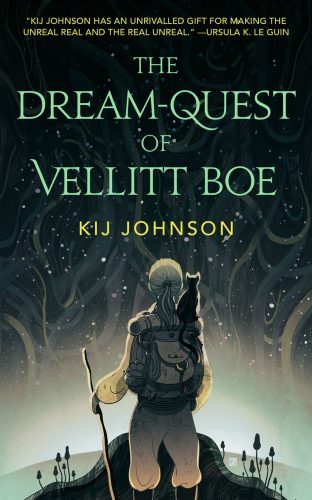

A strange and delightful congruity connects The Dream-Quest of Vellitt Boe with the last Hugo-nominated book I reviewed, The Ballad of Black Tom. Both reach back toward Lovecraft, grab hearty handfuls of story, and mold it into works that manage the requisite respect for the author of such incredible tales while openly challenging his prejudices. You can refresh your memory about how Victor LaValle elegantly reframes Lovecraft into a tale of loss and revenge in last month’s review. We’re here today to talk about Kij Johnson’s brilliant, expansive, and enthralling The Dream-Quest of Vellitt Boe.

Most of the story takes place in the same world as Lovecraft’s The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath, complete with the array of fantastical locales and creatures that populate Lovecraft’s dreamlands—that’s right folks, there are zoogs, gugs, and ghouls aplenty in Vellitt Boe. I hadn’t (and still haven’t) read Lovecraft’s Unknown Kadath, but based on some cursory research it’s a bit of an outlier in Lovecraft’s body of work, particularly because it isn’t as macabre as his other works. In fact, some people on the web called it “uplifting.” I’ll reserve my own commentary until such time as I have read the book in question. I’m certain that an intimacy with Unknown Kadath would make reading Vellitt Boe all the sweeter, but even without knowing the context in which the story’s told, Vellitt Boe is a terrific work of writing.

In contrast to where LaValle took Lovecraft’s horror, Kij Johnson took the wonder and fantasy of Lovecraft and cranked them up to eleven. But there’s a stunning reversal at the heart of the story, specifically to do with wonder, which I’ll go into further below. Where LaValle took Lovecraft’s bigotry and reformed it into a story of loss and cathartic revenge, Johnson looked at the complete lack of women—his dismissive sexism—in Unknown Kadath and, occupying the space he glossed over, tells a story about adventure, fear, wonder, and the subversion of the divine.

Vellitt Boe, the eponymous protagonist of the novella, is a professor at the Women’s College at Ulthar (one of the dreamlands). That there is a Women’s College at all, and the hinted-at fragility of its existence, is clear commentary on Lovecraft’s treatment of women in general, but it isn’t a focal point of the story. It’s the foundation upon which the stakes are built for Vellitt and, though they remain throughout the story, an odd distance grows between Vellitt and the College she defends; her need to protect the school, its staff, and its students never falters, but her personal connection to it wanes.

A brief overview of the story’s events before I dive into what captivated me about it: Vellitt Boe is awoken in the middle of the night to discover that one of her brightest students, Clarie Jurat, has run away with a man from the waking world. As Clarie’s father is one of the benefactors of the Women’s College, this scandalous event could have far-reaching ramifications, up to (and including) the closing of the Women’s College. Vellitt volunteers to go after Claire and return her to the College, and sets off immediately. At this point, we know little of Vellitt aside from her role at the school and tidbits about her personality. As she travels, we learn more about her past and her passions—the story is a story of growth and change that is inspired by (and mirrored in) her adventure. Ultimately, the quest takes Vellitt out of the dreamlands and into the waking world where she finds Clarie and delivers her message—that Clarie must return to the dreamlands. That she must go home. It so happens that, because of the quest itself, Vellitt is barred from returning to the dreamlands. She is unable to go home.

Connection to home, or a lack thereof, is a recurring theme in the story, and there’s a kind of inverse relationship between Vellitt’s fading connection to her home and the overall story arc. As she travels, we learn that Vellitt lived an adventurous and nomadic youth, finally settling at Ulthar and hanging up her traveling cloak and boots for what she thought would be the remainder of her life. But at 55 and back on the road, Vellitt feels the breath of new life in her, and though she sees how she has aged since her traveling years, she realizes that while she was happy at Ulthar, she was stagnating. She was home at Ulthar. But she’s at home on the road—at home at the helm of her own moment-to-moment experience.

As she travels, she’s presented with difficult trials, and each is surmounted with the intervention of Vellitt’s own lived experience. The people she traveled with, the loves and abuses and terrors and strengths of her youth, they all inform her and propel her in strength toward finding her goal, which happens to be restricting that selfsame adventurous streak in a young girl. Vellitt feels for Clarie, for her desire to see the waking world, but she knows that tragedy could befall the Women’s College if this one girl’s thirst for adventure isn’t curbed. The sacrifices she must make so that the progress women made in that world wouldn’t be nullified. It’s a conundrum. It’s thought provoking and gives pause.

Before I spoil the whole book for you, I’d like to talk about one more thing I found particularly compelling about The Dream-Quest of Vellitt Boe: The dreamlands are extraordinary, vivid, and magical. To us—and to waking-world dreamers who visit—it is a fantastical delight. In many respects it is to Vellitt and Clarie, but it is home. Having both been involved with dreamers, they yearn to see the waking world, with its infinite sky of billions of stars, with its enormous scale and properly behaved physics. A tessellating sky that’s something between paper maché and silken lacework is beautiful, but limited. Through the eyes of Vellitt, the awesome landscape of the dreamlands is dimmed, and when she finally opens her eyes in the waking world, a Wisconsin blue sky on a clear day holds the majesty of all the prismatic crystalline cliff-sides you can imagine. The simplicity—mundanity, even—of the real world isn’t replaced. Rather, it is seen from a different perspective, and I was as enchanted with the infinite sky, one I’ve seen every day for my whole life, as Vellitt when she first saw it.

The Dream-Quest of Vellitt Boe is available on Amazon.